Climate Change & Energy

No answers for Ghanaian fishery observer’s family months after suspected death

Source: Mongabay.com - May 2, 2024

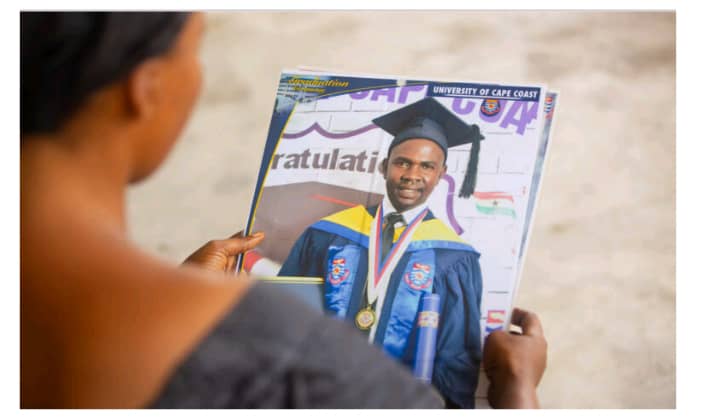

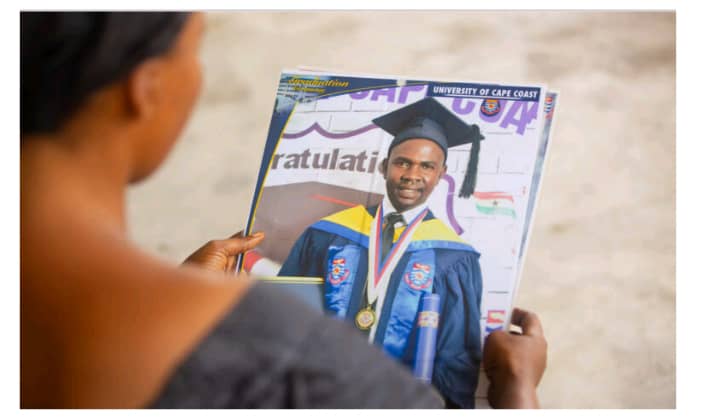

Hagar Kudzorzdi Abayateye, wife of missing fisheries observer Samuel Abayateye, looks at photos of her husband. Image by Gideon Anku for Mongabay.

The brother of a Ghanaian fisheries observer who went missing from his assigned vessel last October says the family has received no information from the authorities investigating the case. Yohane Abayateye tells Mongabay the family is now considering legal action to compel the Ghana Police Service to release the findings of its investigation, especially the DNA test results that could confirm the identity of a headless body that washed ashore in December.

Samuel Abayateye, a 38-year-old father of two, was assigned to the Marine 707, a Ghana-flagged pole-and-line tuna-fishing vessel owned and operated by World Marine Company Ltd. The company, based in the fishing port of Tema, has stated it has 50% South Korean and 50% Ghanaian ownership. The company reported Abayateye missing from the vessel on Oct. 30, 2023. A body missing its head, forearms and feet that the family says closely resembled Abayateye washed ashore nearly six weeks later, and the police opened an investigation.

A week after the body was found, the police asked Abayateye’s 100-year-old mother to assist in a DNA test to confirm its identity, which she did, according to Yohane Abayateye. However, the family’s attempts to get the DNA test results from the Ghana Police Service have proved futile, Yohane told Mongabay in an interview.

“We are therefore left with no other choice than to seek the services of a lawyer to file a suit against the Ghana Police Service to compel them to release the results of the DNA test because we strongly believe the decapitated body discovered at the seashore was that of my brother Samuel,” Yohane said.

A week after the body was found, the police asked Abayateye’s 100-year-old mother to assist in a DNA test to confirm its identity, which she did, according to Yohane Abayateye. However, the family’s attempts to get the DNA test results from the Ghana Police Service have proved futile, Yohane told Mongabay in an interview.

“We are therefore left with no other choice than to seek the services of a lawyer to file a suit against the Ghana Police Service to compel them to release the results of the DNA test because we strongly believe the decapitated body discovered at the seashore was that of my brother Samuel,” Yohane said.

According to Yohane, he and a friend discovered the body on Saturday, Dec. 9, 2023, on the shore of a lagoon in the village of Anyamam, where the family lives. He said he was able to identify his brother by the shirt he was wearing and a distinctive mark on his chest.

“So he is the one, and we need his body from the police for burial,” Yohane said.

When contacted by Mongabay for an update on the case, a communications officer with the Ghana Police Service’s Tema Regional Police Command declined to comment, saying the case is still under investigation and the agency would communicate about it at the appropriate time.

When told about the case of Samuel and the reluctance of the Ghana Police Service to release the DNA report to the family, Joseph Kwarteng, a technician at a private laboratory in Accra, expressed surprise in an interview with Mongabay. “Gone were the days when DNA tests carried out in Ghana took a long time, as there are now ultra-modern DNA test machines in the country that could produce results in less than a week,” he told Mongabay in an interview.

“So if after three months the police are still holding on to the DNA test results, then it is not the unavailability of the result that is preventing them from giving the family any update but something different which is not related to DNA,” Kwarteng said.

A dangerous profession

A fishery observer who spoke to Mongabay on condition of anonymity out of fear of intimidation from his employer or the crews of the vessels he works on expressed shock over Abayateye’s death. He said it has sown fear among observers, employees of the government’s Fisheries Commission who monitor and report on illegal fishing by fleets operating in Ghana.

He referenced the case of Emmanuel Essien, a Ghanaian fishery observer who went missing at sea in 2019 and still has not been found.

“It seems there is pattern that anytime [an] observer goes missing, the government failed to act, and this is putting a lot of fear among our people and we are keenly following how they will handle the case of Samuel because many of us now want to resign for the fear of our lives,” he said.

This isn’t the Abayateye family’s first brush with the dangers of the profession, according to Yohane. He said a cousin named Bernard Adi who was also a fisheries observer mysteriously died on the vessel he was working on in 2022. He said the Fisheries Commission told the family Adi died a natural death and confirmed it with an autopsy report, but that the family doubted that account and instead had reason to suspect Adi had been poisoned.

Yohane also said his grandfather told of an uncle who worked as an engineer on a fishing vessel in the 1960s and was murdered by colleagues unhappy he’d been promoted, then cut to pieces and dumped in a gutter.

Yohane Abayateye sits on a fishing boat at Anyamam beach. Image by Gideon Anku for Mongabay.

“So you can see that, even though our family loves to work in the fishing industry, the setbacks are many and that is why we are not going to let the case of Samuel go unpunished,” Yohane said. Mongabay was unable to confirm details of either account

Fisheries observers play an important role in the sustainable management of fish stocks. Commercial fishing vessels are mandated by governments to accept, house and feed independent fisheries observers, who monitor the vessels’ fishing practices and what they catch, Elizabeth Mitchell-Rachin, a board member of the Association for Professional Observers (APO), a nonprofit based in Eugene, Oregon, U.S., told Mongabay in an interview.

Governments rely on observers to provide this information in order to ensure the vessels are operating legally and to monitor what they take from the sea, including target, nontarget and protected species, such as marine mammals, seabirds and sea turtles.

“However, the sticking point is: Where does this information go?” Mitchell-Rachin said. “What laws are in place that allow the governments to act upon these reports?” One of the most common complaints APO receives from observers worldwide is that their reports are not acted upon by authorities, she said.

According to Mitchell-Rachin, observers regularly face assault, harassment, interference, bribery attempts, tampering with their samples, threats to their safety, and withholding of food. Sometimes they witness illegal activity unrelated to fishing, such as drug and human trafficking, she said, which places them in even greater danger for simply bearing witness to these activities.

She said there have been one or two suspicious observer deaths each year since 2015, though there are likely more because observer programs don’t report such occurrences, despite the obvious connection to illegal fishing.

Fishing boats at Anyamam beach. Image by Gideon Anku for Mongabay.

In Samuel Abayateye’s case, Yohane told Mongabay the last time he spoke to his brother was on Oct. 24, less than a week before his disappearance, when the observer called to say he was trying unsuccessfully to reach his supervisor in Marine 707’s home port of Tema to report an incident.

World Marine Company Ltd. has previously been sanctioned, according to news reports. In 2013 it was among 10 companies the Fisheries Commission fined $3.1 million for violating fisheries regulations, and in 2020 the Nigerian government seized the Marine 707 in Nigerian waters; it was later determined it had failed to follow rules around the use of its AIS tracking device.

In a May 1 statement to Mongabay outlining the company’s response to Abayateye’s disappearance, World Marine Company Ltd. wrote: “We immediately reported the incident to the Ghana police after a search at sea proved futile. The observer was seen by the sailors on board the vessel but he was not seen again in the morning. The vessel stopped fishing and docked at the Tema fishing Harbour. The Ghana police mounted massive investigations in the vessel and among all the fifty (50) sailors on board for several days. …His family said they found a headless body along the shore in their hometown and claimed that it was the missing person. The police sent the body to the Ghana Police Hospital in Accra for the necessary medical tests, and we are awaiting the final police report on the matter.”

A parallel investigation

The case is attracting some international attention. Since Mongabay reported on Abayateye’s disappearance in December, 2023, the APO has been asking Ghanaian authorities for updates on their investigations into his case. The group has so far written letters to the Ghana Police Service, the Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development (MoFAD), and World Marine Company Ltd., according Mitchell-Rachin.

A preliminary report from the Ghana Police Service dated Dec. 29, 2023, and shared with the APO by World Marine Company Ltd. stated that a report from the Ghana Standards Authority ruled out any common poison or drugs in a sample of food retrieved from Abayateye’s bunk on the Marine 707 and that the police service was still awaiting the autopsy and the DNA test results after submitting the samples on Dec. 14, 2023.

Mitchell-Rachin expressed surprise at the delay in releasing the results in an interview with Mongabay. “At the very least they should be communicating with the family at every juncture to let them know why there are delays, and what the expected timeline is,” she said.

She expressed hope that Ghanaian authorities would be forthcoming with their responses as the APO moves through what she described as its own difficult inquiry into the circumstances leading to Abayateye’s disappearance.

“Regardless of the precise details of this case, it continues an alarming pattern of fisheries observers going missing in Ghana,” Steve Trent, chief executive officer of the London-based NGO the Environmental Justice Foundation, told Mongabay via email.

He said the fact that neither the vessel operators nor the government can account for Abayateye and Essien’s disappearances showcases the urgent need for action to protect observers.

“Tuna is entering international supply chains from a fishery where 2 observers have disappeared from foreign-owned industrial vessels in the last 5 years,” Trent said. “While Ghana must take action now, so too should importing countries, starting with adopting the Charter for Fisheries Transparency.”

Yohane Abayateye sits on a fishing boat at Anyamam beach. Image by Gideon Anku for Mongabay.

Yohane Abayateye sits on a fishing boat at Anyamam beach. Image by Gideon Anku for Mongabay.

Fishing boats at Anyamam beach. Image by Gideon Anku for Mongabay.

Fishing boats at Anyamam beach. Image by Gideon Anku for Mongabay.

Hagar Kudzorzdi Abayateye, wife of missing fisheries observer Samuel Abayateye, looks at photos of her husband. Image by Gideon Anku for Mongabay.

Hagar Kudzorzdi Abayateye, wife of missing fisheries observer Samuel Abayateye, looks at photos of her husband. Image by Gideon Anku for Mongabay.

Yohane Abayateye sits on a fishing boat at Anyamam beach. Image by Gideon Anku for Mongabay.

Yohane Abayateye sits on a fishing boat at Anyamam beach. Image by Gideon Anku for Mongabay.

Fishing boats at Anyamam beach. Image by Gideon Anku for Mongabay.

Fishing boats at Anyamam beach. Image by Gideon Anku for Mongabay.