Climate Change & Energy

Forest Declaration Assessment reveals a forest paradox

Source: Mongabay.com - October 23, 2025

File Photo

The world’s forests tell two stories at once. Even as chainsaws advance, new trees are rising in their wake.

More than 11 million hectares of tropical moist forest—an area roughly the size of Cuba—were in some stage of natural regrowth between 2015 and 2021, according to the Forest Declaration Assessment 2025. Latin America shows the most dramatic increase, with regrowth up 750%, and tropical Asia not far behind at 450%. The forest, it seems, remembers how to heal.

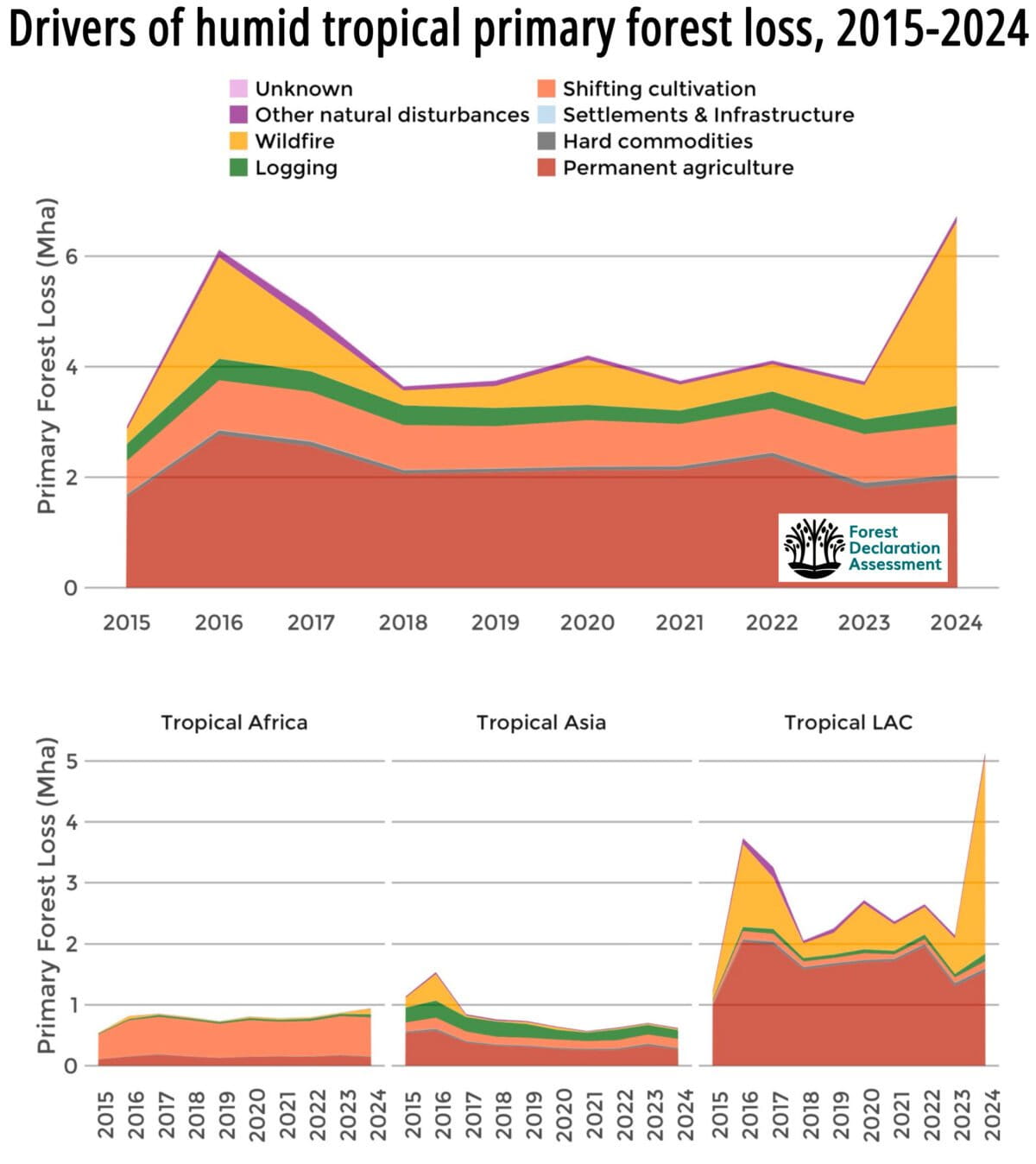

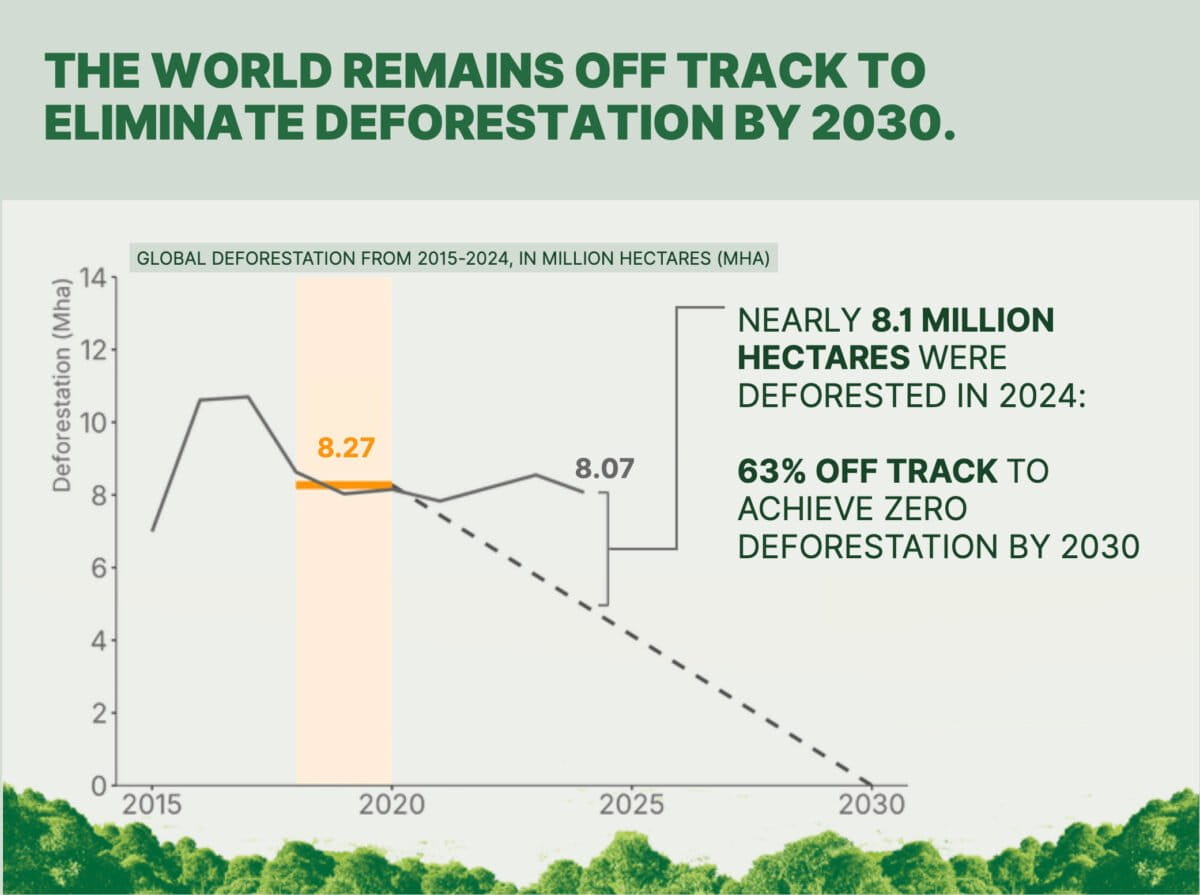

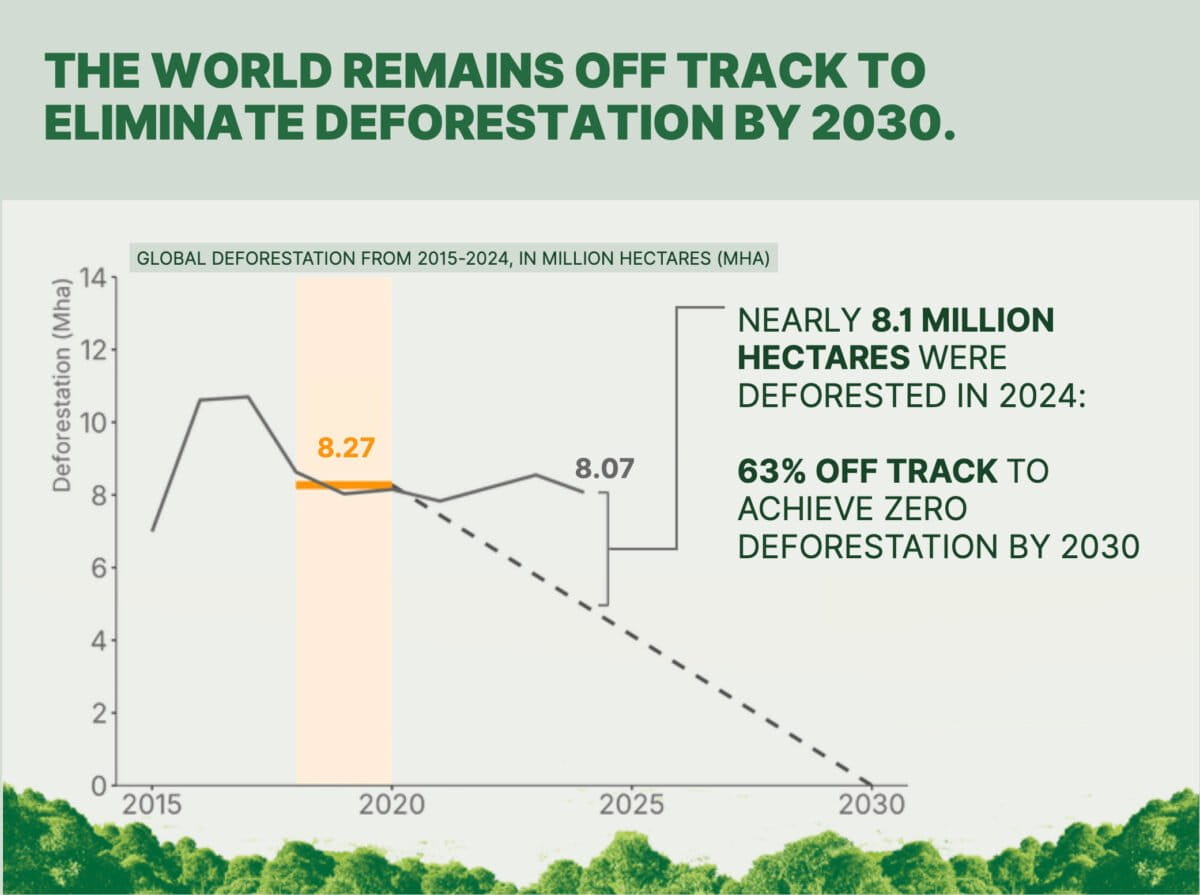

But this recovery story conceals a deeper contradiction. Deforestation has not slowed. The same assessment finds that in 2024 roughly 8.1 million hectares of forest were cleared worldwide—almost exactly the level seen at the decade’s start and 63% off track from the trajectory needed to reach the pledge of “zero deforestation by 2030.”

“Global forests remain in crisis,” the report concludes, midway through what was meant to be the decisive decade.

The paradox is simple: regeneration is rising because destruction continues. “Tropical forests wouldn’t be regrowing if they weren’t cleared in the first place,” explained Erin Matson, the assessment’s lead author. “An increase in regrowth is often correlated to an increase in loss.” Fires, drought, and agricultural expansion keep pushing the boundary between life and ash. Each flare-up opens space for new shoots, even as it drains the ecosystem’s ability to recover.

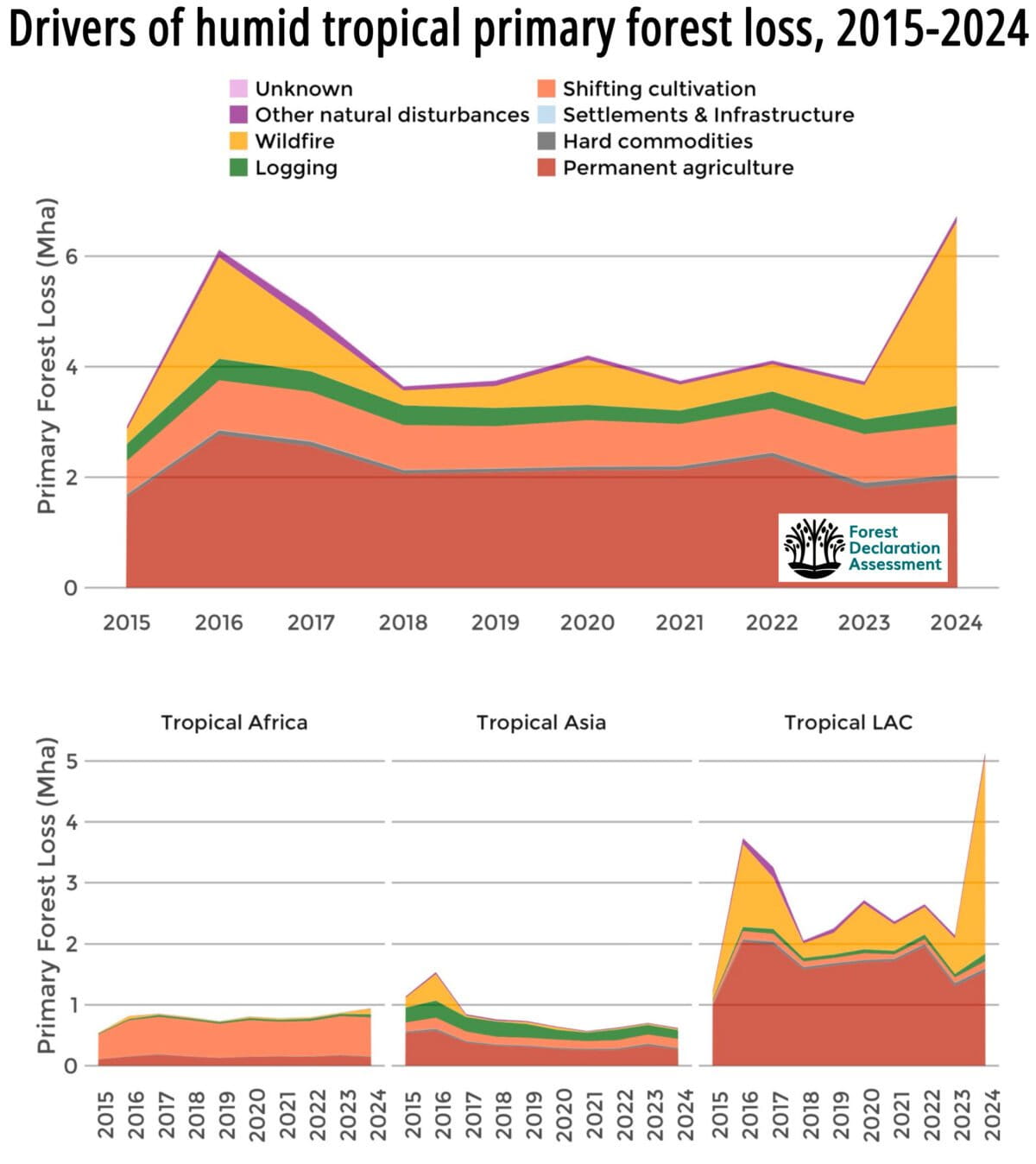

Nowhere is this clearer than in the Amazon. During the 2023-24 El Niño, nearly 150,000 forest fires were recorded each month of the dry season—seven times more than in any previous El Niño. NASA’s Sassan Saatchi noted that “even though they’re reducing deforestation, their forest loss is still really high.” The fires emitted more greenhouse gases than some industrialized nations, turning one of Earth’s greatest carbon stores into a source of emissions. Bolivia lost almost a tenth of its remaining intact moist forests; degradation there alone accounted for nearly a third of all tropical-forest carbon emissions that year.

Since 1990, about 51 million hectares of tropical moist forest have regenerated, but more than half lie in zones of high deforestation pressure. Between 2015 and 2023, roughly 260,000 hectares of secondary growth were again cleared or degraded. This churn of destruction and renewal creates a misleading symmetry: satellite images show greenery returning, yet much of it is short-lived, repeatedly disturbed before ecological maturity.

The scale of the problem defies the pledges made with fanfare in Glasgow in 2021, when 127 countries vowed to halt and reverse forest loss by 2030. Four years later, the numbers have scarcely budged. To stay on course, global deforestation should have fallen to 5 million hectares a year by 2024; instead it remains above 8 million. At this rate, the world will miss the target by a wide margin. The assessment’s authors calculate that the pace of clearing must halve within a single year to realign with the goal—a scenario no analyst deems plausible.

Primary forests, the ancient, carbon-dense ecosystems that take centuries to form, continue to vanish fastest. Some 6.7 million hectares were lost in 2024, releasing 3.1 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalents—about 150% of the U.S. energy sector’s annual emissions. In tropical biodiversity hotspots, tree-cover loss within Key Biodiversity Areas rose 47% from 2023. The dominant force behind all this remains agriculture, responsible for 86% of global deforestation over the past decade. From cattle pasture in Latin America to oil-palm and rubber plantations in Southeast Asia, permanent agriculture continues to replace forests despite corporate “zero-deforestation” promises.

The economic logic that fuels clearance dwarfs efforts to protect or restore. Public finance for forest protection and restoration averaged just $5.9 billion a year—compared with the $409 billion in annual subsidies supporting large-scale industrial agriculture. At current levels, spending on forests would need to increase twentyfold to approach the $117–$299 billion a year that the assessment estimates is required to meet the 2030 goal.

Yet within the grim arithmetic of loss, the regrowth data hint at possibility. Natural regeneration is cheap, scalable, and in many places already under way without deliberate intervention. If spared from new clearings, young secondary forests can rapidly sequester carbon and rebuild habitat. Forests aged 20–40 years remove carbon at their highest rates, and protecting them can deliver up to eight times more carbon benefit per hectare than planting new trees. As the assessment notes, “Protecting these young secondary forests is as critical as preserving primary and pristine forests.”

Still, monitoring such recovery remains a technical headache. Regrowth is gradual, patchy, and hard to distinguish from plantation forestry. The report’s authors describe the global estimate as a “best guess,” constrained by fragmented data and inconsistent national definitions. But even rough figures show that restoration, broadly defined, covers barely 0.3% of the planet’s theoretical forest-restoration potential. A decade into the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, that fraction is sobering.

The tension between destruction and renewal has a long lineage in forest history. Across the tropics, logged or burned land often sprouts again, only to be felled once more when commodity prices rise. In such cycles, regrowth becomes a symptom, not a solution—a sign of disturbance rather than recovery. Forests are resilient but not infinite; repeated clearing erodes soils, dries microclimates, and invites fire, pushing ecosystems toward thresholds beyond which regrowth stalls.

The paradox is therefore less about the forest’s capacity to regrow than humanity’s capacity to stop cutting it down. Natural regrowth is expanding precisely because loss remains high. The satellite record captures both movements at once: green pixels spreading over scars even as new scars appear nearby. Measured purely in hectares, the balance looks ambiguous; measured in ecological integrity, it is unmistakably negative.

For now, the world’s tropical forests are neither advancing nor retreating—they are oscillating. Each gain of green conceals a loss of age, structure, and depth. Whether that oscillation can stabilize before it collapses into decline depends less on the forest’s instinct for regeneration than on the world’s appetite for restraint. For the moment, the balance between loss and renewal remains precarious.

File Photo

File Photo